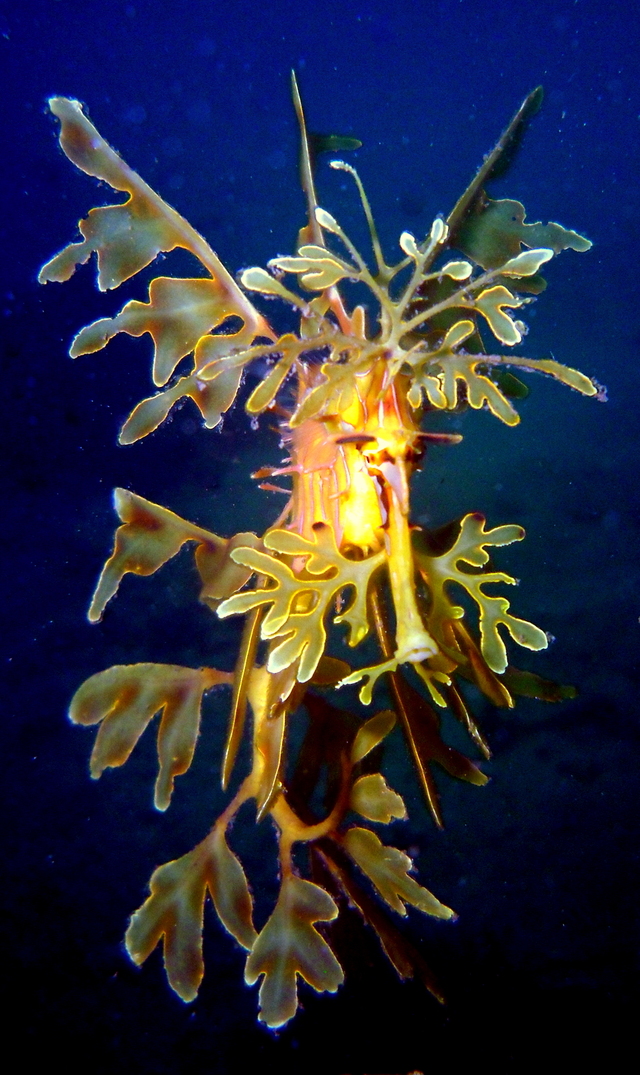

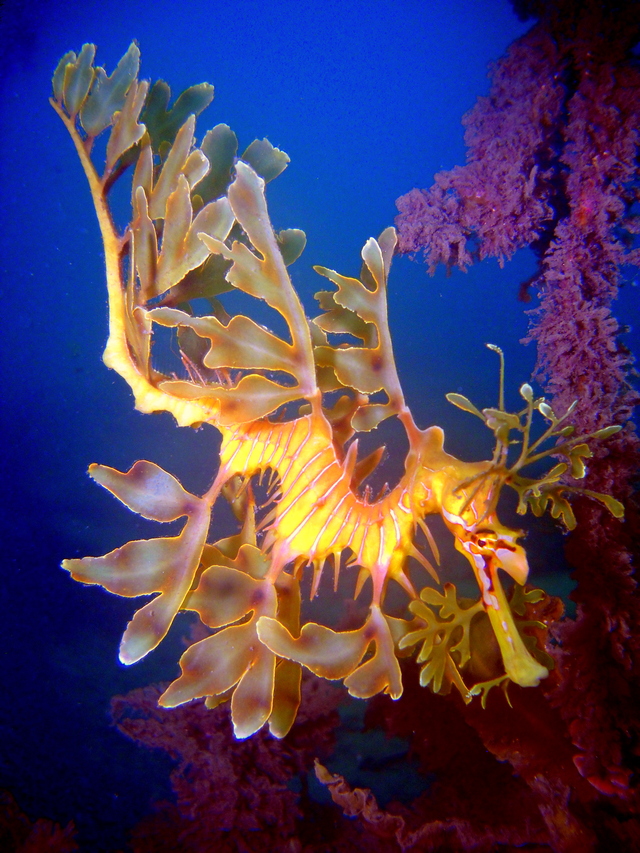

Below Tumby Bay’s iconic jetty, beneath the surface of the Spencer Gulf’s lapping waves, ethereal leafy seadragons sway in the seaweed.

Eyre Peninsula man Jamie ‘Yook’ Coote has been raising awareness of ‘leafies’ since he first spotted one, nearly two decades ago.

That first sighting ignited a passion within him.

Originally from Ceduna, Yook has travelled around, doing stints in Hong Kong and Port Lincoln, and now settled in Tumby Bay for the second time, he has been diving for more than 25 years.

“I’d just always wanted to do it, I’ve always been a water baby,” he said.

“I started out diving recreationally, just rocky outcrops, different beaches, I’d go exploring different spots mainly around Ceduna; it’s just fun.”

Diving has developed far beyond a hobby for Yook.

He now works at the Dive Shop in Port Lincoln and on the Calypso Star Charters as a decky, doing shark cage-diving and swimming with sea lions tours.

Along with his wife Lyn, after all the travelling, Yook eventually moved to Tumby Bay in 2006, which is when he began to hear whispers of the Tumby Bay Leafy Seadragon (Phycodurus eques).

The Tumby Bay Leafy Seadragon is one of three species of seadragon found only in Australian waters, and nowhere else in the world.

“I thought, ‘Oh yeah, cool, I’ll go down and have a look at some’, but I reckon I did 10 or 12 dives before I found my first one because they’re so bloody hard to find,” he laughed.

“After that it became a bit of a passion to go and find them, to document them, and to take other people to find them and show them what we’ve got on our doorstep.”

Underwater photography was a natural progression from Yook’s admiration of the leafies and drive to share this wonder of nature with the rest of the world.

“I use a little old point and shoot, a Nikon in a housing with an external strobe,” he explained.

Yook remembered a time when a local was in disbelief that he was really photographing leafies from the Tumby Bay jetty, but a couple of years later that same man apologised to him, and became a fellow advocate for protecting the unique species – for Yook, that is what it was all about.

“Knowing where individuals have their own hangouts is helpful, I could go for a dive and try and find new ones, but if I hadn’t found any I’d go to a spot I knew where a big male would always be,” he said.

A memorable moment in Yook’s leafie adventures was when Women Divers Hall of Fame inductee Jayne Jenkins came to Tumby to do a dive with him, on a search for the elusive leafie.

“We found one that day, but then I had to pick up my son from daycare, and when I came back she said she wanted to name the big dominant male, she said, ‘I’m going to name him Archie after your son’… that was pretty cool,” he recalled.

Until about five years ago, Yook said the population of leafies he had observed numbered about 12, but due to an unfortunate incident involving human intervention, the population dropped to about a handful, and Archie had since disappeared.

Leafy seadragons are a protected species and heavy fines apply for any intentional interference or removal of a seadragon from the marine environment.

Major threats include pollution and loss of seagrass, seaweed and general habitat.

Leafies are a unique species in that the male fertilises and incubates the eggs.

“I’d probably watched him for about four years and every year he would be laden with eggs,” Yook described.

“Leafy seadragons have lines on their face like a fingerprint, so I could know which one was which.

“One of the cool things is I had actually documented some of his offspring over the years that I knew were from him – due to the facial markings.”

Going slow and looking hard was Yook’s advice to find a leafie, he said to make sure you do not crowd them, give them space and let them do their thing.

Trained assessors in a long-term Dragon Search South Australia citizen science program have been identifying individual leafy seadragons through thousands of seadragon photos since 2013, taken by more than 100 divers.

Project coordinator Janine Baker said matching images accurately over time told scientists a lot about the seadragons in those nearshore populations, their habitat associations and threatening processes.

“Long-term observations are crucial for understanding the life history of seadragons and threats to populations,” she explained.

“Equally important in that process is a reliable, verifiable method of identifying seadragons from photographs taken over years.

“There is no substitute for combining the first-hand knowledge of divers, with a long-term repository of accurately identified images.”

Ms Baker said divers invested a lot of time, effort and personal resources to find, interact with and photograph seadragons in a respectful, non-harmful way – following the code of conduct developed in SA and now used nationally.

“Without the diving community in South Australia, far less would be known about this unique and threatened southern Australian fish species, and how best to protect populations,” she said.

“The Dragon Search South Australia program has revealed much information about leafy seadragons, including breeding patterns and changes over time, exact gestation period in males, long-term partnerships between seadragons, movement between habitats, damage to individuals – and even which types of injuries are temporary compared with permanent.”

For divers who had spotted a leafie and taken a photo, they could add the sighting to iNaturalist – inaturalist.org/projects/dragon-search-south-australia – so an invitation could be sent to join the Dragon Search SA project page.

“We are particularly interested in gathering more images from Eyre Peninsula, a region where comparatively few records have been provided over the years,” Janine said.

“Small, periodic community grants enable gratuity payments to divers for their imagery. Information on the identity of the individual seadragons is sent back to contributing divers, and also posted on local scuba diving group pages on social media, to further mutual education in the community.

“As well as contributing to long-term research, divers who look out for the named seadragons in their local ‘dive patch’ can help ensure the welfare of these vulnerable animals over time.”

Yook said he believed the population at Tumby Bay could rebuild.

“It’s just going to take time for that to happen, to get the big dominant males that want to stay there and live there,” he said.

“Once they mature they sort of pick a spot and that’s where they’ll stay, we think they live for about 10 to 12 years.

“They’re very very good at hiding, so I recommend diving gear, with free-diving you’ll probably miss them.”

Leafy seadragons mimic the sargassum seaweed that grows along the Tumby Bay foreshore and can grow up to 45 centimetres.

Yook had plenty of recommendations for dive spots around Eyre Peninsula including Brennen’s jetty in Port Lincoln, the national parks, off the rocks at Louth Bay, Davenport Creek, Decres Bay and Laura Bay.

“My wife Lyn has always said, ‘you’re grumpy, you need to go for a dive’,” he laughed.

“She says when I come home I’m like a giddy schoolkid telling them all about everything I’ve seen from the day.

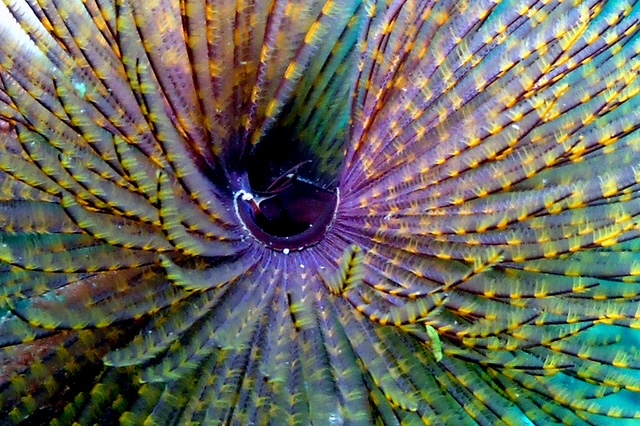

“I haven’t done a dive yet in Tumby Bay where I haven’t found something new; whether it’s a nudibranch, a little fish I haven’t seen before, blue spotted rays, striped pyjama squids and big jellyfish with fish living in them, it’s just enjoyable.”