The inside story of the small Streaky Bay kid who became a horse racing giant.

On one of his many boyish afternoons during the 1980s, out the back of his Nan and Pop’s stables on the far west coast of South Australia, a young lad rides a saddled chaff bag strung between two trees as though his life depends on it.

He rides and whips and commands the hessian feed bag, as he so often does, till dark, while his Pop tends to the horses.

He imagines himself a jockey, like his father, galloping a racehorse down the home straight, the crowd at his back, the wind in his sails.

His name is Kerrin McEvoy.

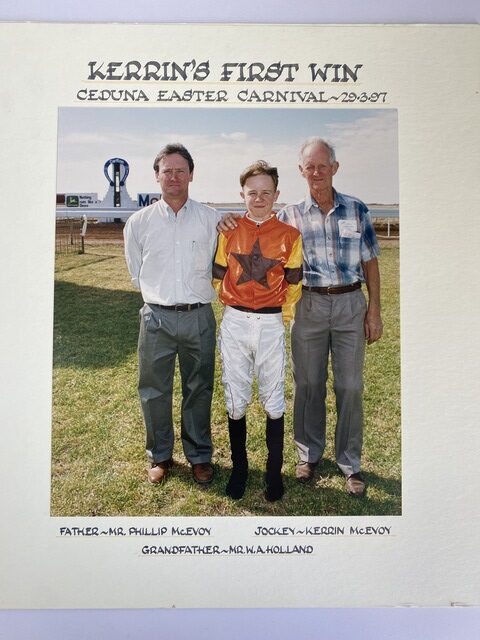

Young Kerrin would have to wait until March 1997 before getting his apprentice licence to jockey, at the age of just 16.

Three weeks later, he’d ride his first winner on a dirt track in Ceduna.

Watching on in the small crowd that day, by the winning post, were Kerrin’s biggest inspirations – his Pop, Bill Holland, and his dad, Phil McEvoy.

Both were former jockeys who had ridden plenty of winners on the Ceduna dirt and beyond. They were proud. They recognised the talent in Kerrin. He was a horseman. A real natural.

They knew it so, but neither could have known what would come next.

Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne Cup Day. It’s the year 2000. Above a thronging crowd, the old clocktower reads 2.59pm – less than a minute to the jump. Kerrin, now 20, is riding in the prestigious event. If he can somehow win, he’ll be the second youngest in history.

The clock strikes three as 120,000 spectators swarm, frantic at the track edge, high on the anticipation. Bill Holland and Phil McEvoy included.

Kerrin is locked and loaded in gate 24, the widest and least likely starting position to win from. His nerves twanging in the saddle. The horse underneath him: a poorly backed gelding called Brew. The barrier doors swing shut. Silence settles. Sweat drips. Flemington beckons.

The gates slap open. Hoofs hit the hallowed turf. Ahead of young Kerrin stretches the two miles of horse racing’s holy grail. To his right, the crowd frenzies. To his left, 21 thoroughbreds surge for position.

By the one mile, he has Brew into midfield. With 500 to run, they are steaming up to sixth. Kerrin knows the horse. Senses it’s a decent spot.

The race swings the final corner and barrels into the home straight. Kerrin sees the clocktower. The crowd. 400 to go. Brew into fifth. Then fourth. Plenty to give.

With 300 to gallop Kerrin lets the beast go. And go he does. By 200, they’re in front, a nose clear. At 100, Brew, and Kerrin, they’re blistering.

The race caller at Flemington hollers over the crowd: “IT’S BREW! Going for home a hundred out – McEvoy wheels the whip and Brew draws away – to win the Melbourne Cup!”

The country kid from Streaky Bay bolts past the fabled post, first by two lengths. He stands upright in his stirrups, one hand on the reins, the other raised skyward, pointer finger rigid, saluting the heaving crowd. Shock and elation written all across him.

Later, critics will hail it one of the great Melbourne Cup rides. To this day, Kerrin rates it among his best long-distance showings.

Within half-a-minute, he’s being interviewed on horseback for live TV.

“I’d like to thank my Pop,” is the first thing he says, catching his breath. “And Mum and Dad and Nanna, and everyone else, they’re all here today.”

“To win the Melbourne Cup in my first ride, it’s just unbelievable – I still don’t know I’ve done it!”

Hours later, in the McEvoys distant Eyre Peninsula hometown, it’s pandemonium at the pub. Everyone knows Kerrin and the small rural township is celebrating. Impulsively, he organises for a hefty tab to be put on the front bar and all his local mates and relatives are revelling.

In town, the day will soon be the stuff of legend. But, as far as the Kerrin McEvoy story goes, it was just the beginning.

Streaky Bay, late March 2022. Today, we’re congregating on the foreshore lawns across from the same pub, 22 years later. Kerrin is here, having flown in this morning from his Sydney home, with his wife and four children.

A large crowd of family and friends and town locals have gathered to witness the unveiling of a life-size statue in his honour.

Since that iconic Melbourne Cup ride more than two decades ago, Kerrin has gone on to become one of Australia’s most eminent and sought-after jockeys.

He’s won the Melbourne Cup three times now: on Almandin in 2016 and Cross Counter in 2018. Only two jockeys in history have won it more.

He’s won the Everest, back-to-back and again in 2020. The Golden Slipper is his. So too the Caulfield Cup – 79 group one victories, more than 2100 wins in total.

He’s lived and ridden extensively overseas, racing for the legendary Godolphin stable in the biggest races across the UK, Europe, Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong and Japan.

To the Streaky Bay community, who largely funded the statue, Kerrin epitomises what can be achieved from way out yonder, here in the country, with the right amount of determination, dedication and talent.

At first, the thought of being immortalised in statue didn’t sit particularly well with the understated jockey, who naturally claims the limelight on horseback, yet is reserved off it.

But, the prospect of leaving a legacy for the youth of his hometown swayed him.

“It’s surreal. It means a lot to have a statue unveiled in your hometown,” he says.

“But there’s one thing I do hope it achieves in coming years – I hope it inspires the young kids to work hard and really push to find a passion they’re interested in and give it 100 per cent, day in, day out.

“I’d like to think they can get some inspiration from it, and remember I was once a skinny kid here, riding my bike home from the jetty of an evening, just like they do.”

Growing up through the 1980s and 1990s in the small coastal outpost of Streaky Bay turned out to be the perfect breeding ground for Kerrin McEvoy.

His dad was a successful jockey at the time, having won almost every cup on Eyre Peninsula.

His pop lived just a few houses up the road on the outskirts of town. Bill was a shearer and a racehorse trainer and out the back of his place lived the family stables.

“I’d go to work at five in the morning,” Kerrin’s dad, Phil, remembers. “And I’d be walking up the hill from our house to the stables and I’d look back in the dark and there’d always be little Kerrin, running up the road.

“I’d send him home, but he’d never go. He’d come up and he knew what to do. His Pop and I, we’d work the horses and when we’d come back, he’d have raked all the yards, have the shit picked up, the water changed and fresh feed ready.”

By the time Kerrin was school age, he was entrenched alongside his pop, and dad, in the daily horse work.

“He got a bit bigger and then he started riding a couple of ponies with us out the track or down the beach, before I’d send him home to shower up and off to school,” Phil says.

“They were great times,” Kerrin recalls fondly. “More often than not I’d be ten minutes late to school, but I think the teachers knew I was doing a bit of work with the horses in the mornings, so they’d turn a blind eye.

“After school, I’d usually rush home and grab the golf sticks or the cricket bat or head off for a swim at the jetty, and then head back up to the stables by about five o’clock, that was when Pop used to do the night feeds.”

The old wooden stables out the back of his Pop’s had become the focal point for Kerrin, where dreams of championing winning racehorses were beginning to meld with significant learnings from his mentors.

“Sometimes, I’d stay the whole school holidays up there at Nan and Pops, just because I wanted to be close to the horses, not that it was far from home, only a few hundred metres,” Kerrin laughs.

“I was always outside emulating a jockey or a horse and there were many hours and weekends spent running around reliving horse races. It was a passion I was bred into.”

The suspended hessian feed bags which young Kerrin would saddle and ride fervently behind the stables needed to be changed weekly, such was the tenacity at which they were ridden.

“We had the chaff bag set up right near the cocky’s cage, and I’d be on there, banging away, making out I was a jockey for hours on end. The old cocky used to love it,” Kerrin says.

In a time and place before aspiring jockeys learnt the ropes on mechanical horses, a chaff bag strung between trees had been the key training apparatus for many a generation of Holland and McEvoy horsemen and women.

“That was the good old traditional way to do it,” Kerrin says.

“You’d learn how to sit on there, like it was a horse, and balance and practice riding using the whip, just like you were a jockey.”

Before long, Kerrin was sinking his teeth into the real deal out at Streaky Bay’s dirt track, under the increasing tutelage of his pop.

“Bill and I started barrier trialing him all the time,” Phil remembers. “He was only tiny, he wasn’t quite strong enough to ride a big racehorse, so he’d jump his pony out and follow, he’d be a furlong back behind us in the dust, choking up, but that’s the way he learnt.”

Bill, once a successful jockey himself, had Kerrin well and truly under his wing by then. The camaraderie was strong.

“Kerrin idolised Bill,” Phil tells me. “He taught him just about everything he knows.”

“He had Kerrin on the chaff bag to get him going, to get his balance and whip, then it was on to the ponies and then one morning he threw him on a racehorse, it looked like he’d been riding them for years.”

“I’d always be hanging off Pop,” Kerrin reflects tenderly.

“He was a great man to be around. He was very patient and a hard worker. I just learnt so much along the way with him and a lot of those things still stand with me today. I wouldn’t be where I am now without him.”

Indeed, Kerrin credits much of his success – including his tenacious hardworking attitude as well as the capacity to remain humble throughout his career – to those country upbringings alongside his bloodline.

“I had some fantastic early years up at the stables with Dad and Pop; it was such a great learning period for me and put me in marvellous stead to become a professional jockey,” he says.

“I was very lucky to have a good grounding and good mentors. I never really saw us being from the country as a deterrent, I was always quite proud of it.”

By the age of 12, Kerrin had begun travelling the eight hours from Streaky Bay to Adelaide by himself, each school holidays.

He would catch the stateline coach out of town, swap buses in Port Augusta, and be picked up by his uncle Tony McEvoy in the city.

Tony was a jockey at the highly rated Lindsay Park stables, owned by distinguished horse trainer Colin Hayes. For the next four years, Kerrin would spend the holidays immersing himself in his first encounters with the professional racing world.

By his 17th birthday – roughly six months after Kerrin rode his maiden winner in Ceduna – the talented young jockey was starting to show signs of outgrowing Eyre Peninsula.

“Bill looked at him one day and he was just progressing way too quick, we had to get him out of here and over to Adelaide,” Phil says.

But in Adelaide, where Kerrin had started a jockey apprenticeship under Russel Cameron, the result was the same.

“Russel rang me one night and said, ‘Phillip, you’ve got to get this kid to Melbourne. Immediately. Straight away. He’s light, riding terrific, his track work is just fantastic’.”

Kerrin went, and after some difficulty settling into the rhythm and intensity of life in Melbourne, he eventually found his feet, some momentum and, rode a couple of winners.

Within 18 months, he’d steer Brew to that famous victory in the 2000 Melbourne Cup.

Soon after, he would attract the attention of Godolphin and be whisked away to live in Dubai and ride the world over, where he’d earn the tag of Australia’s top international jockey.

In 2004, while Kerrin was living in Dubai riding for Godolphin, his pop was tragically bucked off a young horse in Streaky Bay.

Bill’s neck was badly broken in the accident and he was flown to Adelaide, where he was placed on life support.

The family was numb. The day before the fall, Bill had been shearing at a local shed. Now, the 74-year-old could only communicate with medical staff by moving his eyes.

“I got on a plane and came straight home,” Kerrin says. “I still remember going in and seeing him in the hospital, he was on life support, it was daunting.

“I’d been away for eight or nine months of that year, so I hadn’t seen a lot of him leading up to it, it was a very sad period.”

In an interview closer to the accident, Kerrin spoke of his heartbreak: “We are always aware of the risks, but it was cruel how the game we all love took him away.”

Nearly a year to the day of Bill’s passing, Kerrin had a serious fall during a race at Flemington. He was hospitalised with severe facial injuries which required significant plastic surgery.

Almost 12 months after that, he fell again at Flemington. This time the result was more critical – bleeding on the brain.

Then, in 2010, Kerrin had the most serious accident of his career. A fractured T6 vertebrae in a fall that left him sprawled on the track, motionless.

The road to recovery was long and uncertain. Months in a restrictive back brace, worn 24 hours a day, was followed by extensive rehabilitation and nagging self-doubt.

“It took a good 12 months to get confidence back in my body and my mind,” Kerrin says.

“I was unsure if my body would be able to withstand the rigours of race riding again, it took a lot of hard work and persistence to get back to the top level.”

Following the adversity of brain and spinal traumas, Kerrin would remarkably rise again and, in the process, etch himself in the record books as a true racing immortal.

In a rich vein of form between 2016 and 2020, then in his late 30s, he recorded five wins across Australia’s two most prestigious horse races: the Melbourne Cup and the Everest.

Speaking with Kerrin in 2018, following his record third Melbourne Cup – just weeks after he’d gone back-to-back at the Everest – respected racing commentator Bruce McAvaney summed up Kerrin’s standing in the sport: “Two Melbourne Cups is enormous,” McAvaney said trackside. “But when you go to three you actually elevate – in many ways, Kerrin, you’ve gone from a great to an all-time great.”

Today, I ask the champion if he’s surprised to still have the drive to compete at the highest level.

“No, not really,” he says. “It’s been a continued love for horse racing, the passion is strong.”

“I have a young family of my own now, coming into their early teen years, and they take a lot of pride and enjoyment in what their Dad does.”

Just like Kerrin used to.

Streaky Bay, Eyre Peninsula. It’s late March 2022 and Kerrin is finishing a speech at his statue unveiling.

In his address to the youth of his hometown, with his own kids listening in the crowd, he encourages them to all find their passion.

To “dream big,” he urges. “And go hard.”

Years and years earlier, young Kerrin is in class at the local school, in year 1, working at his desk.

He’s writing about horses, like usual, when his teacher suggests that perhaps he choose a different topic, for a change.

Six-year-old Kerrin stops what he’s doing.

He looks up at his teacher.

“Why?” he asks.

“I’m going to win the Melbourne Cup one day.”

– This story was first published in SA Weekend magazine as ‘The Natural’